Coronavirus’ business impact: Evolving perspective | McKinsey

Click here for full article.

COVID-19: Implications for business

March 2020

Current perspectives on the coronavirus outbreak

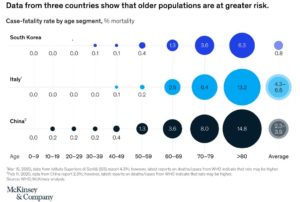

At the time of writing, there have been more than 160,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and more than 6,000 deaths from the disease. Older people, especially, are at risk (Exhibit 1). More than 100 countries have reported cases; 60 have confirmed local transmission. Even as the number of new cases in China is falling (to less than 20, on some days), it is increasing exponentially in Italy (doubling approximately every four days). China’s share of new cases has dropped from more than 90 percent a month ago to less than 1 percent today.

Exhibit 1

WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020. In its message, it balanced the certainty that the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) will inevitably spread to all parts of the world, with the observation that governments, businesses, and individuals still have substantial ability to change the disease’s trajectory. In this note, we describe emerging archetypes of epidemic progressions; outline two scenarios for the pandemic and its economic effects; and observe some of the ways that business can improve on its early responses.

Our perspective is based on our analysis of past emergencies and our industry expertise. It is only one view, however. Others could review the same facts and emerge with a different view. Our scenarios should be considered only as two among many possibilities. This perspective is current as of March 16, 2020. We will update it regularly as the outbreak evolves.

Archetypes for epidemic progression

Many countries now face the need to bring widespread community transmission of coronavirus under control. While every country’s response is unique, there are three archetypes emerging—two successful and one not—that offer valuable lessons. We present these archetypes while acknowledging that there is much still to be learned about local transmission dynamics and that other outcomes are possible:

- Extraordinary measures to limit spread. After the devastating impact of COVID-19 became evident in the Hubei province, China imposed unprecedented measures—building hospitals in ten days, instituting a “lockdown” for almost 60 million people and significant restrictions for hundreds of millions of others, and using broad-based surveillance to ensure compliance—in an attempt to combat the spread. These measures have been successful in rapidly reducing transmission of the virus, even as the economy has been restarting.

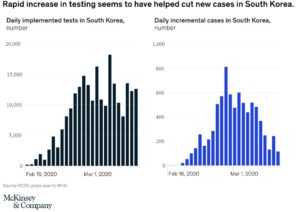

- Gradual control through effective use of public-health best practices. South Korea experienced rapid case-count growth in the first two weeks of its outbreak, from about 100 total cases on February 19 to more than 800 new cases on February 29. Since then, the number of new cases has dropped steadily, though not as steeply as in China. This was achieved through rigorous implementation of classic public-health tools, often integrating technology. Examples include rapid and widespread deployment of testing (including the drive-through model) (Exhibit 2), rigorous contact tracing informed by technology, a focus on healthcare-provider safety, and real-time integrated tracking and analytics. Singapore and Taiwan appear to have applied a similar approach, also with broadly successful results.

Exhibit 2

- Unsuccessful initial control, leading to overwhelmed health systems. In some outbreaks where case growth has not been contained, hospital capacity has been overwhelmed. The disproportionate impact on healthcare workers and lack of flexibility in the system create a vicious cycle that makes it harder to bring the epidemic under control.

There are also other approaches being considered (such as a focus on reaching herd immunity); the impact of these is unclear.

Two scenarios

Based on new information that emerged last week, we have significantly updated and simplified our earlier scenarios. A number of respected institutions are now projecting very high case counts. The most pessimistic projections typically give the virus full credit for exponential growth but assume that humans will not respond effectively—that is, they assume that many countries will fall into the third archetype described earlier. We believe this is possible but by no means certain. The scenarios below outline two ways that the interplay between the virus and society’s response might unfold and the implications on the economy in each case. Exhibit 3 lays out a number of critical indicators that may provide early notice of which scenario is unfolding.

Delayed recovery

Epidemiology. In this scenario, new case counts in the Americas and Europe rise until mid-April. Asian countries peak earlier; epidemics in Africa and Oceania are limited. Growth in case counts is slowed by effective social distancing through a combination of national and local quarantines, employers choosing to restrict travel and implement work-from-home policies, and individual choices. Testing capacity catches up to need, allowing an accurate picture of the epidemic. The virus proves to be seasonal, further limiting its spread. By mid-May, public sentiment is significantly more optimistic about the epidemic. The Southern Hemisphere winter sees an uptick in cases, but by that point, countries have a better-developed playbook for response. While the autumn of 2020 sees a resurgence of infections, better preparedness enables continued economic activity.

Economic impact. Large-scale quarantines, travel restrictions, and social-distancing measures drive a sharp fall in consumer and business spending until the end of Q2, producing a recession. Although the outbreak comes under control in most parts of the world by late in Q2, the self-reinforcing dynamics of a recession kick in and prolong the slump until the end of Q3. Consumers stay home, businesses lose revenue and lay off workers, and unemployment levels rise sharply. Business investment contracts, and corporate bankruptcies soar, putting significant pressure on the banking and financial system.

Monetary policy is further eased in Q1 but has limited impact, given the prevailing low interest rates. Modest fiscal responses prove insufficient to overcome economic damage in Q2 and Q3. It takes until Q4 for European and US economies to see a genuine recovery. Global GDP in 2020 falls slightly.

Prolonged contraction

Epidemiology. In this scenario, the epidemic does not peak in the Americas and Europe until May, as delayed testing and weak adoption of social distancing stymie the public-health response. The virus does not prove to be seasonal, leading to a long tail of cases through the rest of the year. Africa, Oceania, and some Asian countries also experience widespread epidemics, though countries with younger populations experience fewer deaths in percentage terms. Even countries that have been successful in controlling the epidemic (such as China) are forced to keep some public-health measures in place to prevent resurgence.

Economic impact. Demand suffers as consumers cut spending throughout the year. In the most affected sectors, the number of corporate layoffs and bankruptcies rises throughout 2020, feeding a self-reinforcing downward spiral.

The financial system suffers significant distress, but a full-scale banking crisis is averted because of banks’ strong capitalization and the macroprudential supervision now in place. Fiscal and monetary-policy responses prove insufficient to break the downward spiral.

The global economic impact is severe, approaching the global financial crisis of 2008–09. GDP contracts significantly in most major economies in 2020, and recovery begins only in Q2 2021.

Responding to COVID-19: What companies are missing

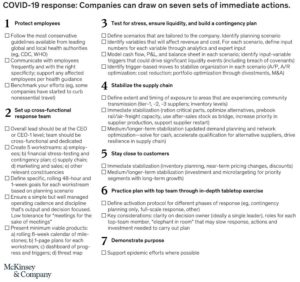

Our conversations with hundreds of companies around the world on COVID-19 challenges have allowed us to compile a view of the major work streams that companies are pursuing (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4

While this list is fairly comprehensive, some companies are taking other steps. However, we have seen evidence that many companies are finding it hard to get the major actions right. We have consistently heard about five challenges.

Having an intellectual understanding isn’t the same as internalizing the reality

Exponential case-count growth is hard to internalize unless you have experienced it before. Managers who haven’t experienced this or been through a “tabletop” simulation are finding it difficult to respond correctly. In particular, escalation mechanisms may be understood in theory, but companies are finding them hard to execute in reality, as the facts on the ground don’t always conform to what it says in the manual. Crisis case studies are replete with examples of managers who chose not to escalate, creating worse issues for their institutions.

Employee safety is paramount, but mechanisms are ineffective

Policy making at many companies is scattershot, especially at those that haven’t yet seen the coronavirus directly. Many, such as professional-services and tech companies, lean very conservative: their protection mechanisms often add to a perception of safety without actually keeping people safer. For instance, temperature checks may not be the most effective form of screening, given that the virus may transmit asymptomatically. Asking employees to stay at home if they are unwell may do more to reduce transmissibility. Such policies are more effective if employees receive compensation protection—and insulation from other consequences too.

Some companies aren’t thinking through the second-order effects of their policies. For example, a ban on travel without a concomitant work-from-home policy can make the office very crowded, leading to higher risk of transmission. Others are adopting company-wide policies without thinking through the needs of each location and each employee segment.

Optimism about the return of demand is dangerous

Being optimistic about demand recovery is a real problem, especially for companies with working-capital or liquidity shortages and those veering toward bankruptcy. Troubled organizations are more likely to believe in a faster recovery—or a shallower downturn. Facing up to the possibility of a deeper, more protracted downturn is essential, since the options available now, before a recession sets in, may be more palatable than those available later. For example, divestments to provide needed cash can be completed at a higher price today than in a few weeks or months.

Assumptions across the enterprise are misaligned

Some companies are pursuing their coronavirus responses strictly within organizational silos (for example, the procurement team is driving supply-chain efforts, sales and marketing teams are working on customer communications, and so on). But these teams have different assumptions and tend to get highly tactical, going deep in their own particular patch of weeds rather than thinking about what other parts of the company are doing—or about what might come next.

The near term is essential, but don’t lose focus on the longer term (which might be worse)

Immediate and effective response is, of course, vital. We think that companies are by and large pursuing the right set of responses, as shown in Exhibit 4. But on many of these work streams, the longer-term dimensions are even more critical. Recession may set in. The disruption of the current outbreak is shifting industry structures. Credit markets may seize up, in spite of stimulus. Supply-chain resilience will be at a premium. It may sound impossible for management teams that are already working 18-hour days, but too few are dedicating the needed time and effort to responses focused on the longer term.

The coronavirus crisis is a story with an unclear ending. What is clear is that the human impact is already tragic, and that companies have an imperative to act immediately to protect their employees, address business challenges and risks, and help to mitigate the outbreak in whatever ways they can.

For the full set of our latest perspectives, please see the attached full briefing materials, which we will update regularly. We welcome your comments and questions at coronavirus_client_response@mckinsey.com.

For more of the latest information on COVID-19, please see reports from the European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and WHO; and thelive tracker of global cases from Johns Hopkins University.

COVID-19: Briefing note, March 9, 2020

A range of outcomes is possible. Decision makers should not assume the worst.

Less than ten weeks have passed since China reported the existence of a new virus to the World Health Organization. This virus, now known as SARS-CoV-2, causing COVID-19 disease, spread quickly in the city of Wuhan and throughout China. The country has experienced a deep humanitarian challenge, with more than 80,000 cases and more than 3,000 deaths. COVID-19 progressed quickly beyond China’s borders. Four other major transmission complexes are now established across the world: East Asia (especially South Korea, with more than 7,000 cases, as well as Singapore and Japan), the Middle East (centered in Iran, with more than 6,500 cases), Europe (especially the Lombardy region in northern Italy, with more than 7,300 cases, but with widespread transmission across the continent), and the United States, with more than 200 cases. Each of these transmission complexes has sprung up in a region where millions of people travel every day for social and economic reasons, making it difficult to prevent the spread of the disease. In addition to these major complexes, many other countries have been affected. Exhibit 1 (see an updated version of the exhibit here) offers a snapshot of the current progress of the disease and its economic impact.

The next phases of the outbreak are profoundly uncertain. In our view, the prevalent narrative, focused on pandemic, to which both markets and policy makers have gravitated as they respond to the virus, is possible but underweights the possibility of a more optimistic outcome. In this briefing note, we attempt to distinguish the things we know from those we don’t, and the potential implications of both sets of factors. We then outline three potential economic scenarios, to illustrate the range of possibilities, and conclude with some discussion of the implications for companies’ supply chains, and seven steps businesses can take now to prepare.

Our perspective is based on our analysis of past emergencies and on our industry expertise. It is only one view, however. Others could review the same facts and emerge with a different view. Our scenarios should be considered only as three among many possibilities. This perspective is current as of March 9, 2020. We will update it regularly as the outbreak evolves.

What we know, and what we are discovering

What we know. Epidemiologists are in general agreement on two characteristics of COVID-19:

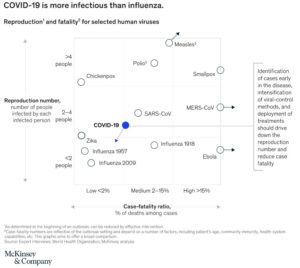

- The virus is highly transmissible. Both observed experience and emerging scientific evidence show that the virus causing COVID-19 is easily transmitted from person to person. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the virus’s reproduction number (the number of additional cases that likely result from an initial case) is between 1.6 and 2.4, making COVID-19 significantly more transmissible than seasonal flu (whose reproduction number is estimated at 1.2 to 1.4) (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

- The virus disproportionately affects older people with underlying conditions. Epidemiologists Zunyou Wu and Jennifer McGoogan analyzed a report from China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that looked at more than 72,000 cases and concluded that the fatality rate for patients 80 and older was seven times the average, and three to four times the average for patients in their 70s. 1 Other reports describe fatality rates for people under 40 to be 0.2 percent.

What we are still discovering. Three characteristics of the virus are not fully understood, but are key variables that will affect how the disease progresses, and the economic scenario that evolves:

- The extent of undetected milder cases. We know that those infected often display only mild symptoms (or no symptoms at all), so it is easy for public-health systems to miss such cases. For example, 55 percent of the cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship did not exhibit significant symptoms (even though many passengers were middle-aged or older). But we don’t know for sure whether official statistics are capturing 80 percent, 50 percent, or 20 percent of cases.

- Seasonality. There is no evidence so far about the virus’s seasonality (that is, a tendency to subside in the northern hemisphere as spring progresses). Coronaviruses in animals are not always seasonal but have historically been so in humans for reasons that are not fully understood. In the current outbreak, regions with higher temperatures (such as Singapore, India, and Africa) have not yet seen a broad, rapid propagation of the disease.

- Asymptomatic transmission. The evidence is mixed about whether asymptomatic people can transmit the virus, and about the length of the incubation period. If asymptomatic transfer is a major driver of the epidemic, then different public-health measures will be needed.

These factors notwithstanding, we have seen that robust public-health responses, like those in China outside Hubei and in Singapore, can help stem the epidemic. But it remains to be seen how these factors will play out and the direct impact they will have. The economic impact too will vary considerably.

Economic impact

In our analysis, three broad economic scenarios might unfold: a quick recovery, a global slowdown, and a pandemic-driven recession. Here, we outline all three. We believe that the prevalent pessimistic narrative (which both markets and policy makers seem to favor as they respond to the virus) underweights the possibility of a more optimistic outcome to COVID-19 evolution.

Quick recovery

In this scenario, case count continues to grow, given the virus’s high transmissibility. While this inevitably causes a strong public reaction and drop in demand, other countries are able to achieve the same rapid control seen in China, so that the peak in public concern comes relatively soon (within one to two weeks). Given the low fatality rates in children and working-age adults, we might also see levels of concern start to ebb even as the disease continues to spread. Working-age adults remain concerned about their parents and older friends, neighbors, and colleagues, and take steps to ensure their safety. Older people, especially those with underlying conditions, pull back from many activities. Most people outside the transmission complexes continue their normal daily lives.

The scenario assumes that younger people are affected enough to change some daily habits (for example, they wash hands more frequently) but not so much that they shift to survival mode and take steps that come at a higher cost, such as staying home from work and keeping children home from school. A complicating factor, not yet analyzed, is that workers in the gig economy, such as rideshare drivers, may continue to report to work despite requests to stay home, lest they lose income. This scenario also presumes that the virus is seasonal.

In this scenario, our model developed in partnership with Oxford Economics suggests that global GDP growth for 2020 falls from previous consensus estimates of about 2.5 percent to about 2.0 percent. The biggest factors are a fall in China’s GDP from nearly 6 percent growth to about 4.7 percent; a one-percentage-point drop in GDP growth for East Asia; and drops of up to 0.5 percentage points for other large economies around the world. The US economy recovers by the end of Q1. By that point, China resumes most of its factory output; but consumer confidence there does not fully recover until end Q2. These are estimates, based on a particular scenario. They should not be considered predictions.

Global slowdown

This scenario assumes that most countries are not able to achieve the same rapid control that China managed. In Europe and the United States, transmission is high but remains localized, partly because individuals, firms, and governments take strong countermeasures (including school closings and cancellation of public events). For the United States, the scenario assumes between 10,000 and 500,000 total cases. It assumes one major epicenter with 40 to 50 percent of all cases, two or three smaller centers with 10 to 15 percent of all cases, and a “long tail” of towns with a handful or a few dozen cases. This scenario sees some spread in Africa, India, and other densely populated areas, but the transmissibility of the virus declines naturally with the northern hemisphere spring.

This scenario sees much greater shifts in people’s daily behaviors. This reaction lasts for six to eight weeks in towns and cities with active transmission, and three to four weeks in neighboring towns. The resulting demand shock cuts global GDP growth for 2020 in half, to between 1 percent and 1.5 percent, and pulls the global economy into a slowdown, though not recession.

In this scenario, a global slowdown would affect small and mid-size companies more acutely. Less developed economies would suffer more than advanced economies. And not all sectors are equally affected in this scenario. Service sectors, including aviation, travel, and tourism, are likely to be hardest hit. Airlines have already experienced a steep fall in traffic on their highest-profit international routes (especially in Asia–Pacific). In this scenario, airlines miss out on the summer peak travel season, leading to bankruptcies (FlyBe, the UK regional carrier, is an early example) and consolidation across the sector. A wave of consolidation was already possible in some parts of the industry; COVID-19 would serve as an accelerant.

In consumer goods, the steep drop in consumer demand will likely mean delayed demand. This has implications for the many consumer companies (and their suppliers) that operate on thin working-capital margins. But demand returns in May–June as concern about the virus diminishes. For most other sectors, the impact is a function primarily of the drop in national and global GDP, rather than a direct impact of changed behaviors. Oil and gas, for instance, will be adversely affected as oil prices stay lower than expected until Q3.

Pandemic and recession

This scenario is similar to the global slowdown, except it assumes that the virus is not seasonal (unaffected by spring in the northern hemisphere). Case growth continues throughout Q2 and Q3, potentially overwhelming healthcare systems around the world and pushing out a recovery in consumer confidence to Q3 or beyond. This scenario results in a recession, with global growth in 2020 falling to between –1.5 percent and 0.5 percent.

Supply-chain challenges

For many companies around the world, the most important consideration from the first ten weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak has been the effect on supply chains that begin in or go through China. As a result of the factory shutdowns in China during Q1, many disruptions have been felt across the supply chain, though the full effects are of course still unclear.

Hubei is still in the early phases of its recovery; case count is down, but fatality rates remain high, and many restrictions remain that will prevent a resumption of normal activity until early Q2. In the rest of China, however, many large companies report that they are running at more than 90 percent capacity as of March 1. While some real challenges remain, such as lower than usual availability of migrant labor, there is little question that plants are returning back to work quickly.

Trucking capacity to ship goods from factories to ports is at about 60 to 80 percent of normal capacity. Goods are facing delays of between eight and ten days on their journey to ports.

The Baltic Dry Index (which measures freight rates for grains and other dry goods around the world) dropped by about 15 percent at the onset of the outbreak but has increased by nearly 30 percent since then. The TAC index, which measures air-freight prices, has also risen by about 15 percent since early February.

In the next few months, the phased restart of plants outside Hubei (and the slower progress of plants within Hubei) is likely to lead to challenges in securing critical parts. As inventories are run down faster, parts shortages are likely to become the new reason why plants in China cannot operate at full capacity. Moreover, plants that depend on Chinese output (which is to say, most factories around the world) have not yet experienced the brunt of the initial Chinese shutdown and are likely to experience inventory “whiplash” in the coming weeks.

Perhaps the biggest uncertainty for supply-chain managers and production heads is customer demand. Customers that have prebooked logistics capacity may not use it; customers may compete for prioritization in receiving a factory’s output; and the unpredictability of the timing and extent of demand rebound will mean confusing signals for several weeks.

Responding to COVID-19

In our experience, seven actions can help businesses of all kinds. We outline them here as an aid to leaders as they think through crisis management for their companies. These are only guidelines; they are by no means exhaustive or detailed enough to substitute for a thorough analysis of a company’s particular situation.

Protect your employees. The COVID-19 crisis has been emotionally challenging for many people, changing day-to-day life in unprecedented ways. For companies, business as usual is not an option. They can start by drawing up and executing a plan to support employees that is consistent with the most conservative guidelines that might apply and has trigger points for policy changes. Some companies are actively benchmarking their efforts against others to determine the right policies and levels of support for their people. Some of the more interesting models we have seen involve providing clear, simple language to local managers on how to deal with COVID-19 (consistent with WHO, CDC, and other health-agency guidelines) while providing autonomy to them so they feel empowered to deal with any quickly evolving situation. This autonomy is combined with establishing two-way communications that provide a safe space for employees to express if they are feeling unsafe for any reason, as well as monitoring adherence to updated policies.

Set up a cross-functional COVID-19 response team. Companies should nominate a direct report of the CEO to lead the effort and should appoint members from every function and discipline to assist. Further, in most cases, team members will need to step out of their day-to-day roles and dedicate most of their time to virus response. A few workstreams will be common for most companies: a) employees’ health, welfare, and ability to perform their roles; b) financial stress-testing and development of a contingency plan; c) supply-chain monitoring, rapid response, and long-term resiliency (see below for more); d) marketing and sales responses to demand shocks; and e) coordination and communication with relevant constituencies. These subteams should define specific goals for the next 48 hours, adjusted continually, as well as weekly goals, all based on the company’s agreed-on planning scenario. The response team should install a simple operating cadence and discipline that focuses on output and decisions, and does not tolerate meetings that achieve neither.

Ensure that liquidity is sufficient to weather the storm. Businesses need to define scenarios tailored to the company’s context. For the critical variables that will affect revenue and cost, they can define input numbers through analytics and expert input. Companies should model their financials (cash flow, P&L, balance sheet) in each scenario and identify triggers that might significantly impair liquidity. For each such trigger, companies should define moves to stabilize the organization in each scenario (optimizing accounts payable and receivable; cost reduction; divestments and M&A).

Stabilize the supply chain. Companies need to define the extent and likely duration of their supply-chain exposure to areas that are experiencing community transmission, including tier-1, -2, and -3 suppliers, and inventory levels. Most companies are primarily focused on immediate stabilization, given that most Chinese plants are currently in restart mode. They also need to consider rationing critical parts, prebooking rail/air-freight capacity, using after-sales stock as a bridge until production restarts, gaining higher priority from their suppliers, and, of course, supporting supplier restarts. Companies should start planning how to manage supply for products that may, as supply comes back on line, see unusual spikes in demand due to hoarding. In some cases, medium or longer-term stabilization may be warranted, which calls for updates to demand planning, further network optimization, and searching for and accelerating qualification of new suppliers. Some of this may be advisable anyway, absent the current crisis, to ensure resilience in their supply chain—an ongoing challenge that the COVID-19 situation has clearly highlighted.

Stay close to your customers. Companies that navigate disruptions better often succeed because they invest in their core customer segments and anticipate their behaviors. In China, for example, while consumer demand is down, it has not disappeared—people have dramatically shifted toward online shopping for all types of goods, including food and produce delivery. Companies should invest in online as part of their push for omnichannel distribution; this includes ensuring the quality of goods sold online. Customers’ changing preferences are not likely to go back to pre-outbreak norms.

Practice the plan. Many top teams do not invest time in understanding what it takes to plan for disruptions until they are in one. This is where roundtables or simulations are invaluable. Companies can use tabletop simulations to define and verify their activation protocols for different phases of response (contingency planning only, full-scale response, other). Simulations should clarify decision owners, ensure that roles for each top-team member are clear, call out the “elephants in the room” that may slow down the response, and ensure that, in the event, the actions needed to carry out the plan are fully understood and the required investment readily available.

Demonstrate purpose. Businesses are only as strong as the communities of which they are a part. Companies need to figure out how to support response efforts—such as by providing money, equipment, or expertise. For example, a few companies have shifted production to create medical masks and clothing.

The checklist in Exhibit 3 can help companies make sure they are doing everything necessary.

Exhibit 3

COVID-19: Briefing note, March 2, 2020

The following is McKinsey’s perspective as of March 2, 2020.

What we know about the outbreak

COVID-19 crossed an inflection point during the week of February 24, 2020. Cases outside China exceeded those within China for the first time, with 54 countries reporting cases as of February 29. The outbreak is most concentrated in four transmission complexes—China (centered in Hubei), East Asia (centered in South Korea and Japan), the Middle East (centered in Iran), and Western Europe (centered in Italy). In total, the most-affected countries represent nearly 40 percent of the global economy. The daily movements of people and the sheer number of personal connections within these transmission complexes make it unlikely that COVID-19 can be contained. And while the situation in China has stabilized with the implementation of extraordinary public-health measures, new cases are also rising elsewhere, including Latin America (Brazil), the United States (California, Oregon, and Washington), and Africa (Algeria and Nigeria). The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has set clear expectations that the United States will experience community transmission, and evidence is emerging that it may be happening already.

While the future is uncertain, it is likely that countries in the four mature transmission complexes will see continued case growth; new complexes may emerge. This could contribute to a perception of “leakage,” as the public comes to believe that the infections aren’t contained. Consumer confidence, especially in those complexes, may erode, and could be further weakened by restrictions on travel and limits on mass gatherings. China will mostly likely recover first, but the global impact will be felt much longer. We expect a slowdown in global growth for 2020. In what follows, we review the two most likely scenarios for economic impact and recovery and provide insights and best practices on how business leaders can navigate this uncertain and fast-changing situation.

Economic impact

In our base-case scenario, continued spread within established complexes, as well as community transmission in new complexes, drives a 0.3- to 0.7-percentage-point reduction in global GDP growth for 2020. China, meanwhile, continues on its path to recovery, achieving a near-complete economic restart by mid-Q2 (in spite of the current challenges of slow permissions and lack of migrant-worker capacity). As other geographies experience continued case growth, it is likely that movement restrictions will be imposed to attempt to stop or slow the progression of the disease. This will almost certainly drive a sharp reduction in demand, which in turn lowers economic growth through Q2 and early Q3. Demand recovery will depend on a slowing of case growth, the most likely cause of which would be “seasonality”—a reduction in transmissions similar to that seen with influenza in the northern hemisphere as the weather warms. Demand may also return if the disease’s fatality ratio proves to be much lower than we are currently seeing.

Regions that have not yet seen rapid case growth (such as the Americas) are increasingly likely to see more sustained community transmission (for example, expansion of the emergency clusters in the western United States). Greater awareness of COVID-19, plus additional time to prepare, may help these complexes manage case growth. However, complexes with less robust health systems could see more general transmission. Lower demand could slow growth of the global economy between 1.8 percent and 2.2 percent instead of the 2.5 percent envisioned at the start of the year.

Unsurprisingly, sectors will be affected to different degrees. Some sectors, like aviation, tourism, and hospitality, will see lost demand (once customers choose not to eat at a restaurant, those meals stay uneaten). This demand is largely irrecoverable. Other sectors will see delayed demand. In consumer goods, for example, customers may put off discretionary spending because of worry about the pandemic but will eventually purchase such items later, once the fear subsides and confidence returns. These demand shocks—extended for some time in regions that are unable to contain the virus—can mean significantly lower annual growth. Some sectors, such as aviation, will be more deeply affected.

In the pessimistic scenario, case numbers grow rapidly in current complexes and new centers of sustained community transmission erupt in North America, South America, and Africa. Our pessimistic scenario assumes that the virus is not highly seasonal, and that cases continue to grow throughout 2020. This scenario would see significant impact on economic growth throughout 2020, resulting in a global recession.

In both the base-case and pessimistic scenarios, in addition to facing consumer-demand headwinds, companies will need to navigate supply-chain challenges. Currently, we see that companies with strong, centralized procurement teams and good relationships with suppliers in China are feeling more confident about their understanding of the risks these suppliers face (including tier-2 and tier-3 suppliers). Others are still grappling with their exposure in China and other transmission complexes. Given the relatively quick economic restart in China, many companies are focused on temporary stabilization measures rather than moving supply chains out of China. COVID-19 is also serving as an accelerant for companies to make strategic, longer-term changes to supply chains—changes that had often already been under consideration.

To better understand which scenario may prevail, planning teams can consider a set of leading indicators like those in the exhibit (see an updated version of the exhibit here).

About the author(s)

Matt Craven is a partner in McKinsey’s Silicon Valley office; Linda Liu is a partner in the New York office, where Matt Wilson is a senior partner; and Mihir Mysore is a partner in the Houston office.